Java Spring is black magic and you should be a dark magician

Hi again from guest writer Matt here! When I say Spring to you, and you think of the season (i.e. rabbits and Easter and such) first and not the Java technology, then this post will probably be very enlightening for you! If you know what Spring is, then hopefully you will learn something.

The tl;dr for the Spring Framework is that it is a massive set of Java libraries. We are going to focus only on a couple pieces of Spring for this piece: Spring IoC (Inversion of Control) and Spring Boot.

Springtime for Java

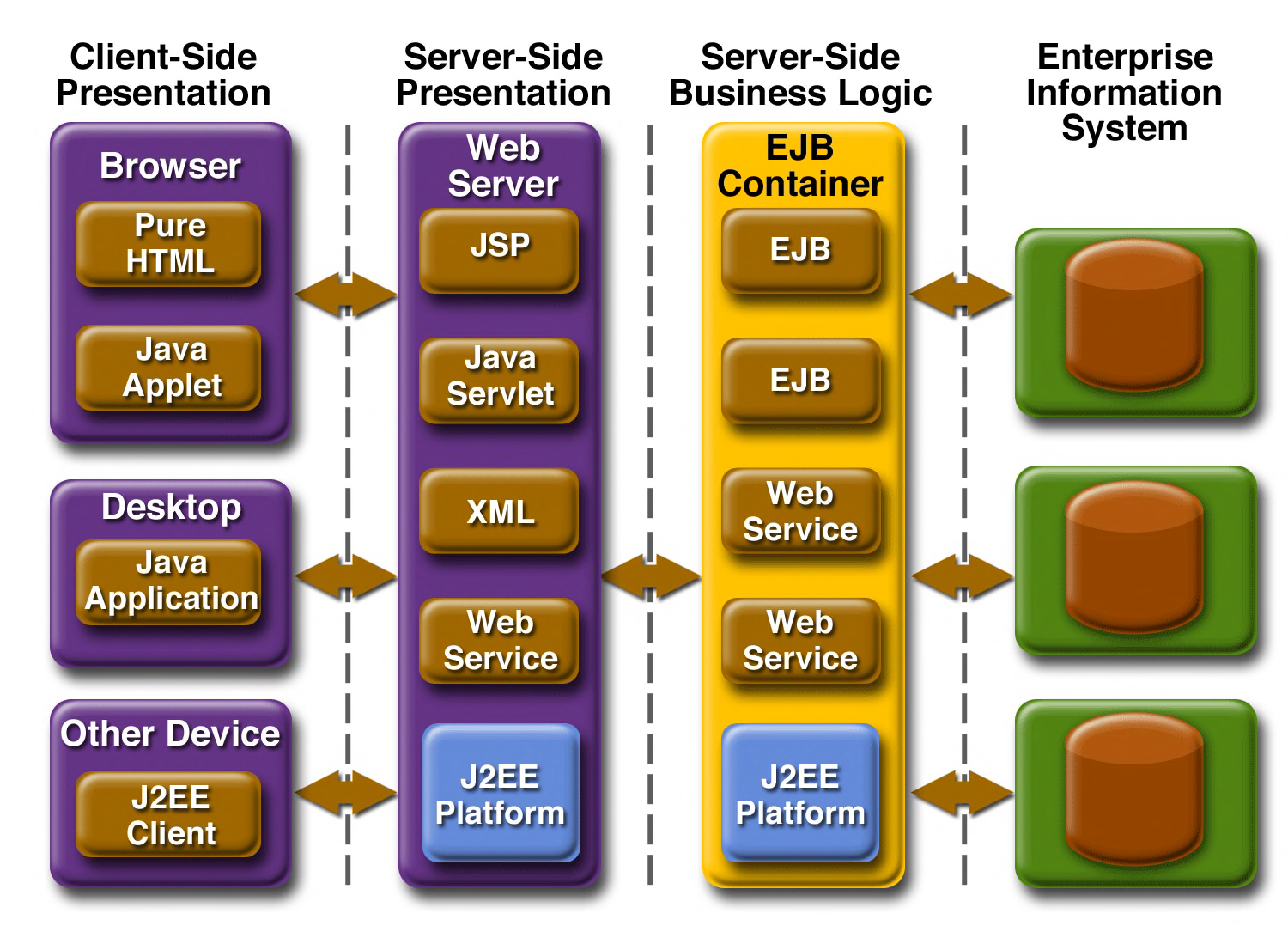

Early Java was strongly characterized by EJB, or Enterprise Java Beans. I won’t beat you over the head with EJB knowledge, but if you are interested here is an article from over 20 years ago on what EJB is. If you don’t feel like reading it, the 50,000 foot view is a way to tier and structure enterprise Java applications. OK maybe it’s the 5,000,000 foot view (that’s ~1000 miles in space).

EJB was a prominent standard in early Java and it is easily paired conceptually with J2EE, Java 2 Platform, Enterprise Edition. If you follow the link you’ll see something like:

If you are horrified when you see JSP and other frontend Java terms, you are not alone! Java frontend stuff has kind of died (thank you Javascript) except for older enterprise apps, so the whole concept of “Java is all you need” has definitely fallen by the wayside.

But in Java’s hour of bean-management-need, another contender emerged. In 2003/4, the Spring framework burst forth onto the scene, and it has gone on to be the lingua franca of dependency management in Java.

Before we talk about Spring, a bit about the terminology.

What is IoC (Inversion of Control)?

…okay and while you’re at it Dependency Injection and Dependency Inversion?

Rapid fire, here is the two sentence oversimplification for each concept:

IoC: Generic term for how an application can call its parts, rather than the parts calling on the application. Don’t call us, we’ll call you (the Hollywood Principle).

Dependency Injection Dependencies are provided at runtime, not compile time, by an application container. Ask and you shall receive.

Dependency Inversion A code style, where abstractions do not depend on details, and objects only depend on objects at their same level of abstraction or higher. Keep things on a need to know basis and use interfaces/implementations to separate layers of abstraction.

What do these look like you may ask? Let’s try and explain without using programming, and instead use a dog walker; let’s call him David.

David can walk any species of Dog, as long as the dogs are provided to David. That means someone outside of David is responsible for delivering the dogs to him to walk. Let’s call that “entity” that is responsible for delivering the dogs Spring.

So Spring is responsible for waking David up in the morning, handing him the dogs, and saying “Okay David, now you can walk the dogs.” David then walks the dogs, in a way Spring is completely unaware of. Once David is done, he returns the dogs to Spring and waits until the next time Spring asks him to walk the dogs. Maybe David has a side hustle as an Uber driver, but Spring doesn’t care.

In this story, control was inverted, because David did not ask anyone for the dogs (he didn’t have to make a phone call or drive over to people’s houses to get the dogs). His friend Spring figured all of that out for him.

In this way, David had to wait until he was handed the dogs, so we can say he had a dependency on the dogs, which was injected i.e. provided by an outside context that David knew very little about.

Lastly, Spring did not care about anything David did with the dogs. Spring didn’t have to depend on how David walked the dogs, just that David was a dog walker and he needed dogs to walk. In fact, maybe David is sick one day, so Spring instead brings the dogs to Frank, another dog walker. Neither Spring, nor any other party involved in the dog walking (the dogs, the people who own the dogs, etc.) are dependent on the inner workings of David or Frank’s dog walking. The only requirement here is that David and Frank fulfill a contract as a dog walker. That is Dependency Inversion.

What does this look like in Spring framework code?

There are essentially two ways to create an application context, one way is via Bean Creation and Importing, the other via Injection/Autowiring of dependencies. I’ll explain each in some detail.

Beans beans, the magical object

Bean is a terrible term, I think, mostly because it is a pun (Java Beans, get it, haha…) and secondly because it doesn’t mean anything on its own, it’s pretty hard to infer what the heck you mean when you say ‘Bean’. Let me try and explain it.

Okay first, a bean is basically the atomic unit of Spring. If you had an application, as we discussed before, with David the dog walker and a bunch of dogs, those would be the “Beans” of the application: each dog and David represent an atomic unit of the application. One can depend on the other (but beware circular dependencies!), and Spring takes care of wiring things together, so you don’t have to make calls to Context.getBean("David") all over your code.

The place where all those beans are stored is called the Application Context.

Beans are relevant to the two ways of creating a Spring app (the direct bean declaration vs. autowiring and components).

The first mechanism we will cover is the explicit approach.

Explicit declaration of beans (@Bean)

The Spring framework, for many versions of Java, depended heavily on XML, primarily because Java did not have any way to pepper metadata into classes. Once annotations were introduced in Java 5, there was a bit of a move away from XML defined beans and into direct annotations. For an example of XML based bean declaration, see this medium post

Continuing on with our example, let’s say I want to make this wonderful app. Here are some code snippets of how I might start out, using the annotation approach instead of the XML or autoconfiguration approaches:

public interface DogWalker {}

public interface Dog {}

public class Pongo implements Dog {}

public class Perdita implements Dog {}

public class David implements DogWalker {

private final List<Dog> dogs;

public David(List<Dog> dogs) {

this.dogs = dogs;

}

}

With our wonderful app, which doesn’t really do anything except set up a skeleton for us, we are ready to build our Spring context. All we need to do is set up a class to house our beans in, annotated with a @Configuration

@Configuration

public class DogAppConfig {

@Bean

public Dog pongo() {

return new Pongo();

}

@Bean

public Dog perdita() {

return new Perdita();

}

@Bean

public DogWalker david(List<Dog> dogs) {

return new David(dogs);

}

}

Some things to note:

- the

@Beanannotation can be left blank, but all Spring beans are named. Their name can either be specified in the@Beanannotation, or can be derived from the method name - You’ll notice that these methods that create Beans return interfaces, not the implementations. This is important to Dependency Inversion, i.e. not depending on details, just honoring a contract.

- Spring is smart enough to wire the pieces together properly, since it can see what implements what. Because Perdita and Pongo are declared as Dogs, when Spring tries to build the application, it will see that David requires all of the Dogs in the app, and will build those beans first, then supply them to David before constructing his bean.

When I say ‘Build/Construct’, I mean Spring calls the bean methods and registers them in the application context (i.e. the bean container). Spring will do this only one time for each bean (i.e. they are singleton) unless the application specifies otherwise (a concept called Scoping, which you can read more about here).

Now with this app, there isn’t really much we can do, considering DogWalkers don’t do anything as of now. But this illustrates the point I think.

To illustrate another point, let’s say we have a dog walker that only walks one dog. Let’s call him Jeff.

public class Jeff implements DogWalker {

private final Dog pongo;

public Jeff(Dog pongo) {

this.pongo = pongo;

}

}

Jeff can only walk Pongo, which means that, within Spring, he’ll declare his dependency on Pongo, but he only takes in a type of “Dog”. How do we know what to inject?

If we do something like

@Bean

public DogWalker jeff(Dog dog) {

return new Jeff(dog);

}

Spring will get mad, telling us that it doesn’t know which dog we want to inject. If one of the beans had happened to be named dog, then it would have just supplied that one (since its name would have matched).

To get around this ambiguity we can use something called @Qualifier (read more here), which allows us to say which type of bean we want.

@Bean

public DogWalker jeff(@Qualifier("pongo") Dog dog) {

return new Jeff(dog);

}

Spring will be much happier in this case, and will be able to look up the dog by name from its registry.

The last piece of this toy problem that is worth considering is what if we wanted to add more dogs? It might start to get messy if we have one file that just has 50 different dogs in it. Spring allows us to separate out our configs, and as long as we include them in our application at runtime, we can declare them in any number of Config files. We can also import them into our current config, so the dependency is explicit

@Configuration

public class OtherDogConfig {

@Bean

public Dog lucky() {

return new Lucky()

}

@Bean

public Dog cadpig() {

return new Cadpig()

}

// TODO: Insert rest of the 101 dalmatians here

}

And in our earlier config we can explicitly import this other config:

@Import({OtherDogConfig.class}

@Configuration

public class AppConfig {

...

}

That about wraps up our discussion of explicit dependencies. How might you use this in a Java app? You would need to either have this Config imported via an xml (for example, with Tomcat) or an annotation, but this leads more into Spring Boot, which we’ll cover in a bit.

Now let’s see the other way of coming about it, using implicit declarations.

Implicit declaration of beans (@Component)

So you don’t like big config files. No one can blame you; you are a more incognito coder. Less is more! Maybe you’d prefer if your DogWalker himself declared his dependencies and advertised himself as a bean using annotations. Enter @Autowired and @Component. Before we get there though, let’s do one quick aside on package scanning.

In the Spring framework, you have the ability to scan a package (i.e. a java package, like com.hello.world) and look for classes to load. This is at the heart of the implicit strategy, and is very much in the spirit of inversion of control (don’t call us, we’ll call you). You can read the docs on package scanning here.

@Component

public class David implements DogWalker {

@Autowired

private final List<Dog> dogs;

}

This is what it looks like in a more implicit world. Let’s break this down:

- Component is a special annotation, which basically says “if you use package scanning, you can count me in as a bean”

- Autowired is an annotation saying “I need this value”, you can put it on a private field and Spring will use Java 7 reflection to supply the value, or you can put it on the constructor, and it will look almost the same as before, without the Config entry of

@Bean

You can also mix and match these different styles. For example, you might still have the config files, but instead you autowire in the dog, i.e.

@Configuration

public class MoreImplicitConfig {

@Autowired

@Qualifier("pongo")

private Dog dog;

// TODO: Autowire all the things

}

This is where we start getting into the black magic. Now you can build an entire app that is loosely coupled and employs the DI/IoC principles, without even creating a Configuration file, or having a very strapped down version of one.

Spring Boot makes it real

There are a lot of tutorials online for Spring Boot, so that’s not what I’m going to do here. E.g. One about component scanning and another one using Thymeleaf (sort of like jekyll but for Java/Spring).

Let’s just take apart two files, which are our Controller class and our Application class. We’ll leave security alone for now, but you can read about it more here.

For the controller:

@RestController

@RequestMapping("/walk")

public class DogWalkingSchedulingController {

@Autowired

private List<DogWalker> dogWalkers;

@GetMapping("/walkers")

public List<DogWalker> getDogWalkers() {

return dogWalkers;

}

@GetMapping("/walkers/{name}")

public DogWalker getDogWalker(@PathVariable String name) {

return dogWalkers.stream()

.filter(walker -> Objects.equals(name, walker.getName()))

.findFirst()

.orElseThrow(NotFoundException::new);

}

}

This controller class has a few useful annotations

- the

@RestControllerannotation, which marks the class as something that can handle requests, and which will get picked up via package scanning. - the

@RequestMapping(), which defines the base endpoint for the controller - the

@GetMappingannotation, which tells Spring this method handles gets on the corresponding path. You can use path parameters with things like{parameter} - the

@PathVariableannotation, which injects the path parameter into the corresponding method

There is a lot of depth to these controllers, but these are then essential annotations. There are other annotations to pass the body in or headers, depending on what you want to handle within the controller.

You’ll notice that our friend @Autowired also made its way here, so we can declare a dependency without having to pass it in the constructor or wire it up in a Configuration class.

For the application class:

@ComponentScan(basePackages = {"com.dog.app"})

@SpringBootApplication

public class Application {

public static void main(String[] args) {

SpringApplication.run(Application.class, args);

}

}

There is a lot going on in there few lines. The most important thing to understand is that the whole class body is really just boilerplate. It’s required so this class can be run. The top two annotations are really the more powerful pieces.

@ComponentScanis an annotation that tells Spring where to look for dependencies, as I mentioned before with package scanning. You can filter out certain pieces as well, or specify explicit packages.@SpringBootApplicationis a monster of an annotation. It really is 3 other important annotations, one of which we’ve already mentioned, the ComponentScan (in this case we are being more explicit). The other two annotations are:@EnableAutoConfiguration, which is a set of implicit configurations that Spring Boot guesses by reading off of the classpath. This is how you can run a web app with so little code, because Spring looks up a bunch of things from its dependencies and uses those AutoConfigurations to launch the Spring Boot app. You can define your own as well, more info here@SpringBootConfigurationwhich is basically just@Configurationbut for Spring Boot apps

Some final black magic

So spring can manage all your dependencies with annotations as your workhorses. But what about really large applications? What about testing? Spring is very well set up to support pulling in beans to tests, using things like @SpringBootTest. But there are plenty of tutorials that you can use to flex your testing muscles. Testing with Spring is worth its own post.

Another good thing to know is that while Spring is creating beans and before it destroys them you can use some special annotations, i.e. @PostConstruct and PreDestroy to specify additional behavior.

For @PostConstruct, you can annotate a method of a class declared as a bean, and this method will be called after calling the constructor and supplying any autowired dependencies.

For @PreDestroy, this will be called before the bean is wiped out (either during shutdown or if the bean is scoped differently). This is usually better for Beans that hold onto a resource, or maybe have a different scope besides Singleton.

The last thing I will leave you with are Profiles. Profiles are ways that you can manage which pieces of an application are deployed. You can annotate configurations with @Profile("prod") or something to that effect, and then set which profiles are active when you boot your application, or when you run tests. You can read more about profiles here.

In closing

I hope you learned something about Spring and the Spring framework. There are many more pieces to it but the Spring Container and Spring Boot components are probably the most popular in the Java community. If you can’t remember the difference between IoC, Dependency Injection and Dependency Inversion, make sure to reread that section. A lot of the tutorials I linked are useful to scan if you are a bit more code curious.

A sample application that has a bit more than the code snippets above can be found here.

Spring is big and if you take the time to figure out what’s going on, you can make it work for you.